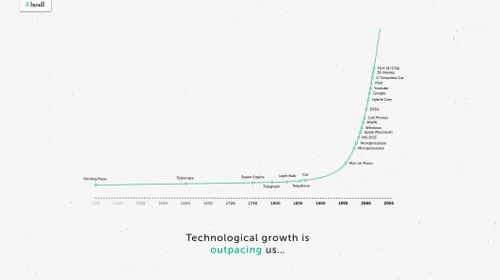

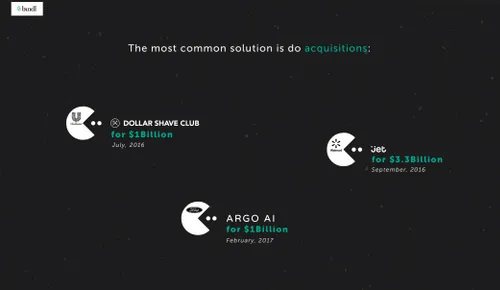

Learn more about how to leverage your corporate assets to stay competitive in a market full of emerging startups.

All you need is the right mindset and structure to beat the startups at their own game

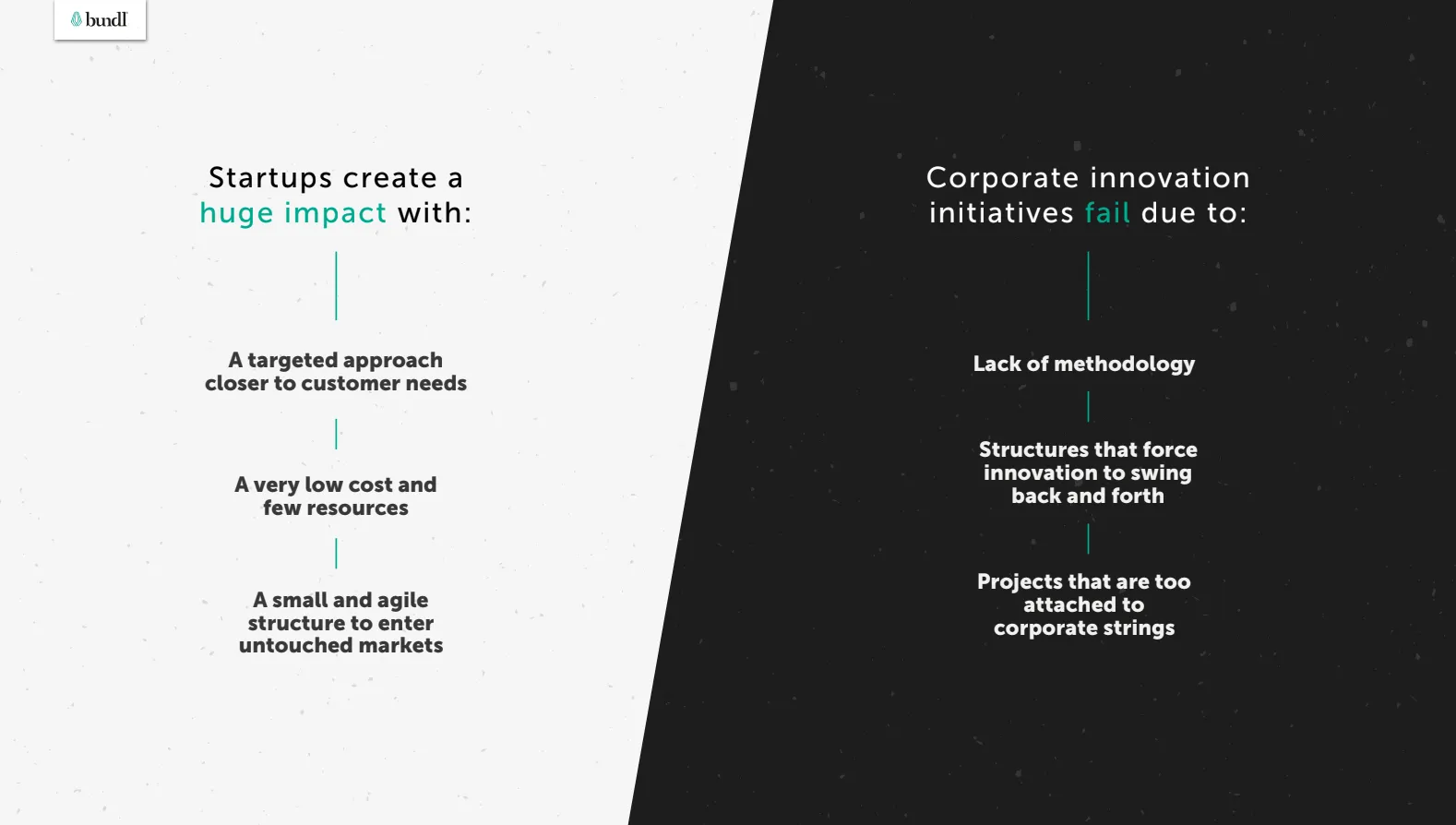

- Learn how to effectively scope, adopt and adapt

- Get 7 key tips to help you disrupt from the inside out

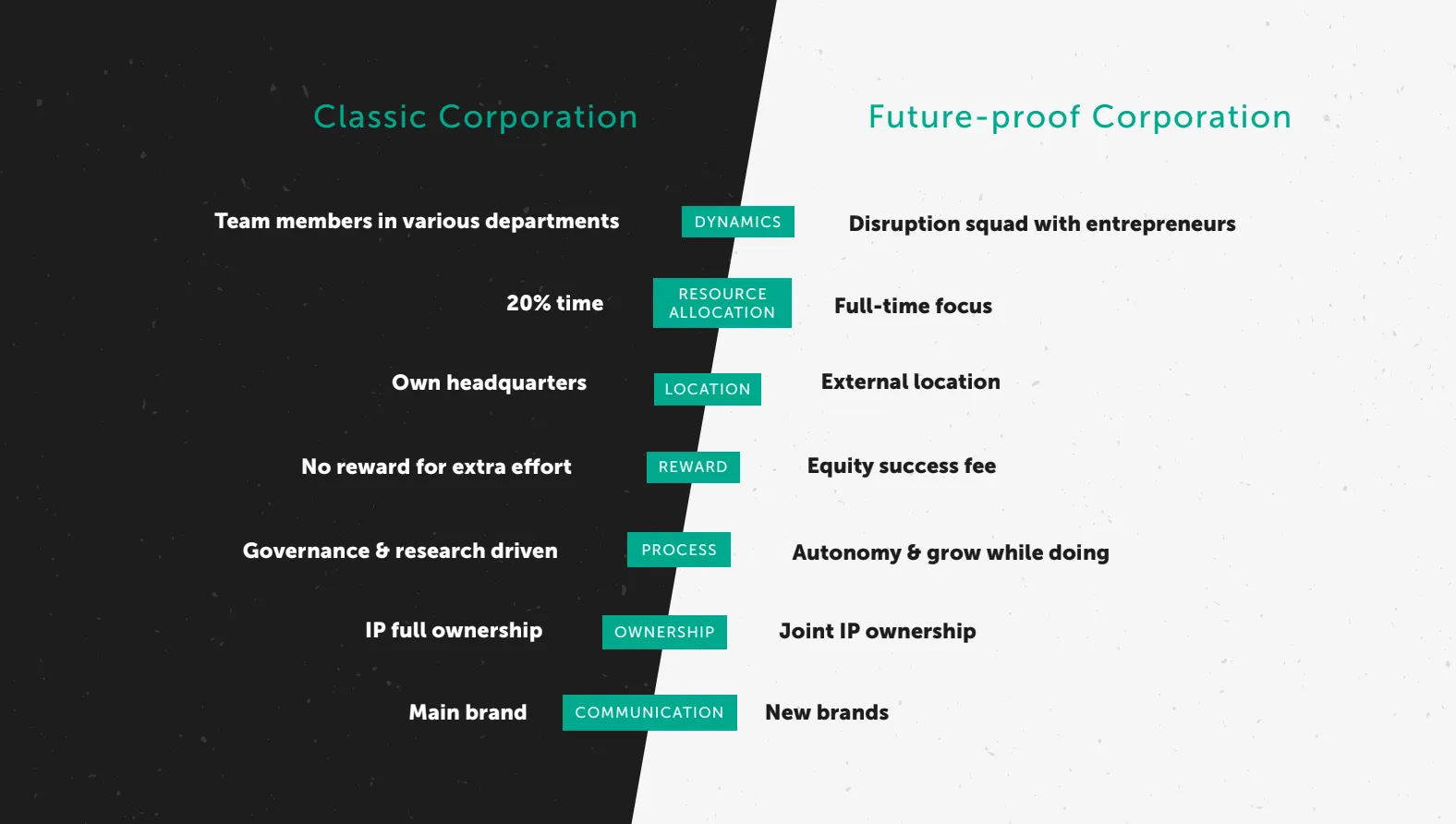

- Go from being a “classic corporation” to be being a “future-proof corporation”

Sneak peek °°

Preview slides to give you taste of the full report.

Report

7 strategies to future proof your business.

Fill in the form to download

This content is exclusive for Bundl Venture Club members.

If you're already a member, contact Leyash for your access link. If not, you can apply for membership below.

Apply for Membership